Why You Don’t Need to Worry (Too Much) About Alzheimer’s If You Have Herpes

For years, scientists have been trying to untangle the complex web of factors that lead to Alzheimer’s disease. Recently, several studies have suggested a possible link between herpes infections and dementia, but experts caution that infections are only one piece of a much larger puzzle.

The Double-Edged Sword of Tau and Beta-Amyloid

A recent study revealed that tau protein helps protect neurons from damage caused by herpes simplex virus (HSV-1) infections. Similarly, beta-amyloid may play a protective role. However, if the infection persists, these proteins can accumulate, forming toxic plaques and tangles that destroy the very neurons they were meant to protect. This accumulation is one of the leading theories behind the development of Alzheimer’s, though infections are far from being the sole cause.

The Search for New Explanations

Decades of research and billions of dollars have yet to yield a highly effective treatment for Alzheimer’s. This has sparked interest in alternative explanations for the disease’s origin, as new insights could lead to better prevention and treatment strategies. A recent analysis by pharmaceutical company Gilead, for example, suggests that preventing herpesvirus infections may be a public health priority for reducing dementia risk.

Using data from nearly 700,000 individuals in the United States, researchers found that herpes labialis (cold sores caused by HSV-1) is associated with a higher risk of Alzheimer’s. The risk increases with age, but the use of antiviral medications seems to reduce the likelihood of developing dementia. However, the researchers emphasized that more studies are needed, and these correlations do not prove that herpes directly causes Alzheimer’s or that antivirals definitively prevent it.

Similarly, another study published in Nature found a 20% lower risk of Alzheimer’s in people vaccinated against herpes zoster (shingles), again suggesting a potential link between herpes viruses and dementia.

One Risk Factor Among Many

Despite these intriguing findings, Alzheimer’s remains an incredibly complex disease. According to Ignacio López-Goñi, a professor of microbiology at the University of Navarra, “80% of the population has had herpes, and the percentage with antibodies against herpes simplex is very high.” In other words, simply being infected with herpes is not enough to cause Alzheimer’s. Genetic factors, like carrying a variant of the APOE gene, and weaker immune systems—common in older adults—also contribute significantly to Alzheimer’s risk.

The Role of Lifestyle in Prevention

Much like cancer, Alzheimer’s develops from a combination of genetic and lifestyle factors. Interestingly, the incidence of Alzheimer’s has decreased by 16% over the past decade, despite an aging population and no major breakthroughs in drug treatments. This decline is largely credited to improvements in cardiovascular health. “What’s good for the heart is good for the brain,” says Josep Maria Argimon, director of Health System Relations at the Fundación and the Barcelonaβeta Brain Research Center.

While Argimon acknowledges the growing evidence linking herpes infections to Alzheimer’s, he cautions that there is still no proof of direct causality. He also does not support mass herpes vaccination as a preventive measure for Alzheimer’s at this point. However, countries like Spain have started vaccinating people over 65 and vulnerable individuals, such as those with blood disorders or who have undergone bone marrow transplants. Any reduction in Alzheimer’s cases would likely be a secondary benefit of these broader health measures.

A Broader Approach to Brain Health

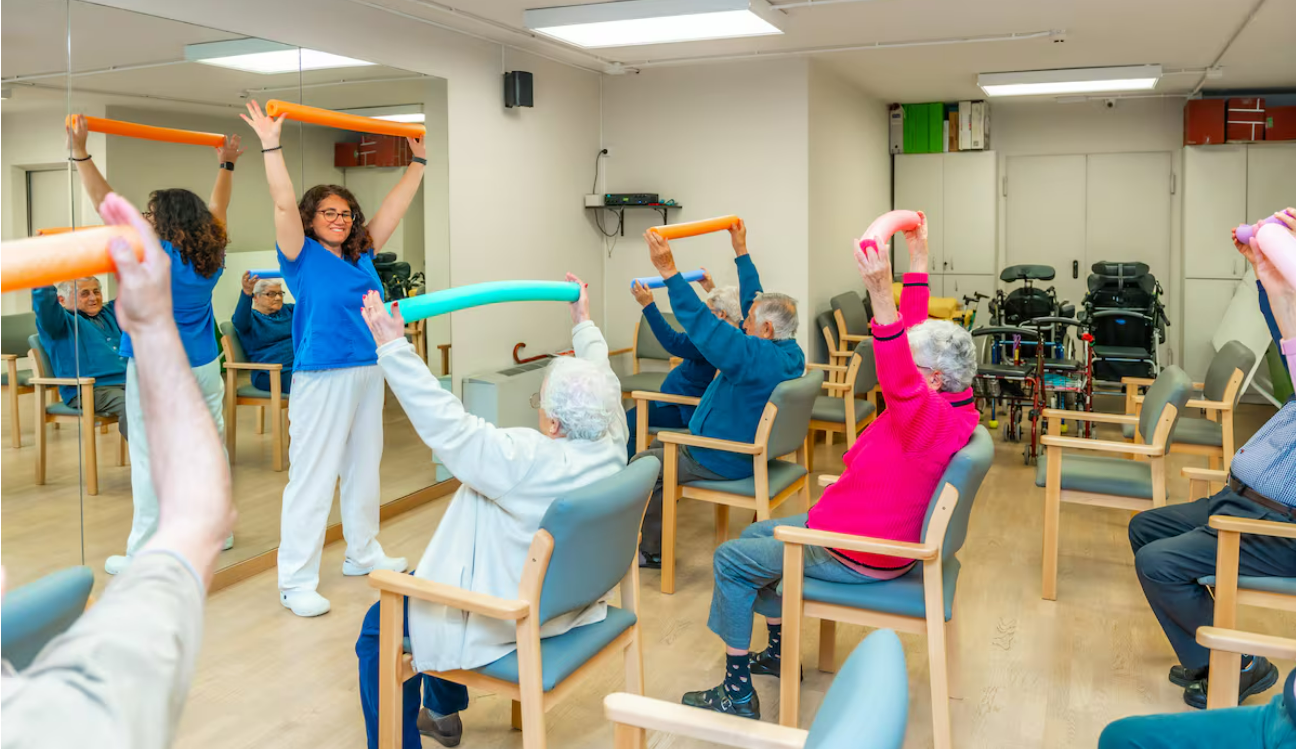

Despite the emerging herpes-Alzheimer’s connection, infections are not currently listed among the preventable risk factors in major medical reviews, such as those published by The Lancet Commission. According to Alberto Rábano, director of the CIEN Foundation Brain Bank in Madrid, controlling known risk factors—such as physical inactivity, hearing loss, depression, and low educational attainment—could reduce dementia cases by up to 45%.

In the meantime, the most effective way to reduce Alzheimer’s risk lies in maintaining overall health. Reducing consumption of processed red meats and ultra-processed foods, staying physically active, building strong social relationships, and managing cardiovascular health can all help delay the onset of dementia and other serious illnesses. While Alzheimer’s remains a complex disease influenced by countless subtle and interconnected factors, many of these risk factors are already well understood—and taking action on them supports not only brain health but a healthier, happier life overall.